Agile Acquisition & Rapid Delivery in Defence – Scanning for Failure

- News Article

- Future tech

- DSEI

“Nobody ever stops or intervenes in a poor project soon enough. The temptation is always to ignore or under-report warning signs and give more time for things to improve to avoid revealing bad news, rather than to intervene decisively at the earliest opportunity.” (Lord Browne of Madingley)[1]

“Nobody ever stops or intervenes in a poor project soon enough. The temptation is always to ignore or under-report warning signs and give more time for things to improve to avoid revealing bad news, rather than to intervene decisively at the earliest opportunity.” (Lord Browne of Madingley)[1]

In the last article, we described what ‘partnering for success’ means. In this article, we explain why and how major defence programmes should ‘scan for failure’.

Failure is all too often wired into complex programmes, so success needs to be won.

Major defence programmes and indeed, all complex programmes, are marred by numerous biases created by mental shortcuts used by programme teams to understand complexity. For example:

- Optimism bias – the tendency to be overly optimistic about the outcome of planned actions, including overestimation of the frequency and size of positive events and underestimation of the frequency and size of negative ones and thus the reason MOD and government approvals seek explicitly to recognise this during investment appraisal and large-scale business cases.

- Availability bias – the tendency to overestimate events where there is greater availability of information. This is particularly prevalent when there is uncertainty and ambiguity arising from the impact of disruptive technology, new adversaries in a military context, contracting information.

The range is extensive and additionally includes strategic misrepresentation, uniqueness bias, planning fallacy and so on. These biases exist because of VUCA, and as described in our previous articles. Volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity cause programme managers, Senior Responsible Owners (SROs) and teams to rely on their established beliefs, preconceptions, and biases to understand their complex programmes. It is a natural human response to VUCA.

It is also a response that can effectively wire in failure. And it means success needs to be actively won.

Historically, the average cost overrun across major UK government programmes is at least 15 per cent. Intervening earlier and more decisively could significantly reduce cost, as well as preserve significant benefits. Major project cancellations and overruns can have huge costs for the UK economy.

Unless active steps are taken to prevent or fix performance problems in a programme, it is highly likely that they will never get back on track and default to benchmark performance. Indeed, as a programme progresses, the ability to make changes to restore performance declines, and the cost to intervene increases. Thus, there is an absolute need for major defence programmes to scan proactively for the tendency or risk of failure. And to do so early.

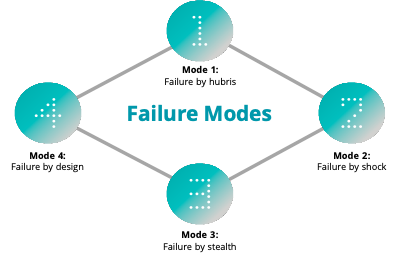

Four modes of failure – hubris, shock, stealth or design.

In our experience, failure in major defence programmes takes four modes depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – the four failure modes of major defence programmes.

- Mode 1: Failure by hubris. Failure by hubris occurs where the initial scope, cost, schedule, and benefits of a major programme are out of touch with the reality of the task. It could be that a project suffered inadequate levels of up-front planning, or a budget cut without a related reduction in scope or benefits. Other causes include ‘entryism’, where budgets are deliberately under-stated and benefits over-stated to get a programme started. Once the organisation is committed to the programme, budgetary increases become the norm. Frequently, too, there is simply optimism bias on the part of the estimators or errors in the estimating process.

- Mode 2: Failure by shock. Failure by shock occurs where there is a significant unexpected disruption to the programme. The slowing of many IT programmes as a result of new legislation on employment (IR35) is a good example of an external shock. Internal shocks include policy or ministerial changes. We also include ‘self-harm’ (e.g. deploying inexperienced people vs. highly experienced major programme practitioners). These are risks that become issues for the programme.

- Mode 3: Failure by stealth. Failure by stealth occurs when relatively minor problems build slowly over the life of a programme until they form a significant barrier to progress. In technology programmes, it is common for constituent projects to end with some technology debt or functionality that could not be delivered at that time which is, taken alone, relatively insignificant: it is the compounding of these over time which leads to failure. Similarly, failure by stealth can be caused by a failure to take advantage of opportunities such as early finish benefits offered by individual projects or workstreams.

- Mode 4: Failure by design. Failure by design occurs where the programme and its extended organisational design (including the contracting and supply strategy) is inappropriate for the nature or desired outcomes of the programme. Common tensions within organisational designs which can prove fundamental obstacles to progress can include lack of alignment of objectives or measures, counterproductive contract terms, over-reliance on individual day-rate contractors who may focus more on programme longevity, and adherence to a single structure more suited to previous phases or tranches. Designs need to evolve with the lifecycle of the programme, but even where this is understood, the requirement to continuously re-design is more onerous than many programme leaders can resource.

Responses and counter-measures.

For each of the modes of failure, a range of counter-measures are available:

- For failure mode 1 (failure by hubris): Overruns in programme estimates are often managed through a ‘predict and provide’ approach, providing more resources to allow the programme to have a greater chance of being delivered within its cost envelope. The HMT Green Book, for example, sets out levels of uplift to be applied to programme estimates to form a cost envelope. However, this is expensive and contributes over time to programmes becoming unaffordable, due to the cost envelope eventually being seen as the de facto target price. For this reason, we advocate ‘predict and prevent’ approaches for the remaining failure modes.

- For failure mode 2 (failure by shock): Shock occurs, by definition, through unexpected events. As such, constant scanning of future opportunities and threats alongside assessment of programme resilience is needed, over and above standard risk management practice. However, it is our experience that even where challenges are identified, they often materialise faster and with greater impact than predicted. and this should encourage the use of scenario analysis (including digital twins) to test strategies.

- For failure mode 3 (failure by stealth): Countering failure by stealth requires constant focus on detail: “sweating the small stuff”. For example, an ongoing innovation team can be deployed to identify and implement new approaches to address threats or opportunities across the programme. Another approach is to implement weekly delay and disruption analysis. Without these approaches, small delays and over-runs are allowed to accumulate, often unnoticed.

- For failure mode 4 (failure by design): Failure by design cannot be addressed through incremental changes. The main counter-measure here is either programme reset, including contract resets, or programme cancellation. It is within the power of most SROs to recommend the cancellation of programmes – but that power is rarely exercised. Although it is an unpalatable option, where the programme business case is no longer deliverable, this may be the best value for money decision. The NAO identified an opportunity for the IPA and HM Treasury to provide further support and guidance to programme decision-makers to help them consider resets in a more structured way and put in place ways to increase the likelihood of a reset being successful.

We plan to publish further elaboration on this perspective in a research piece written by Professor Harvey Maylor, Saïd Business School and Dominic Cook: Delivering the Major Programme Dividend – overcoming sustained false optimism.

At Deloitte, we have a heritage of supporting this type of programme leadership, supporting fundamental programme re-sets and creating the capabilities to look ahead and scan for failure. We bring together strategy, operations, technology and programme delivery, encapsulated in our Programme Aerodynamics® approach.

Programme Aerodynamics® empowers the leaders of today and tomorrow to reimagine problems, build capabilities in anticipation of problems occurring and deliver high-impact solutions.

Authors:

[left to right]

Priyen Patel – Partner focused on strategy in major defence programmes, Deloitte | priypatel@deloitte.co.uk

Dominic Cook – Partner and Major Projects Commercial Lawyer, major programme delivery, Deloitte | dccook@deloitte.co.uk

© 2023 Deloitte LLP. All Rights Reserved. The contents of this article are confidential and the intellectual property of Deloitte LLP and may not be reproduced, redistributed or passed on to any other person in whole or in part without the prior written consent of Deloitte.

This publication contains general information only, and none of the Deloitte member firms are by means of this publication, rendering professional advice or services. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your business, you should consult a qualified professional adviser.

[1] Cabinet Office, Getting a grip: how to improve major project execution and control in government (2013)

Need a pass for DSEI 2023?

-

Latest Defence and Security Capabilities set to be on Display in London as DSEI 2023 Begins

12 Sep 2023Defence and Security Equipment International 2023 (DSEI) opened its doors Tuesday 12th September. DSEI 2023 and DSEI Connect will together host some 1,500 defence and security suppliers – including al ... -

Unlocking the Defence Workforce Ecosystem

05 Sep 2023The UK MOD is facing unprecedented challenges in attracting, growing, and retaining the skills it needs to deliver its mission. The new systems and technologies that the UK is fielding add to this cha ... -

KEY POINTS Rapid modernisation, innovation and technical development is needed for the UK to meet it’s twin priorities of protecting European allies, and stability in the Indo-Pacific. Using innovatio ...

-

DSEI 2023: Royal Navy To Set Up In Receive Mode, To Support Partnering Against Future Threats

04 Sep 2023 Dr Lee WillettThe UK Royal Navy (RN) will have significant presence at the DSEI 2023 exhibition, which is taking place at ExCeL London on 12-15 September. It is also seeking to grasp the engagement opportunity that ... -

Agile Acquisition & Rapid Delivery in Defence – Resilient Teams Harnessing Digital Means

04 Sep 2023“Technology is an extension of human behaviour” – a quote attributed variously, but traceable to the Canadian philosopher, Herbert Marshall McLuhan. Whilst originally referencing the study of media, t ... -

Understanding space: DSEI and UK Space Command

01 Sep 2023 John HillIn March this year, the European Space Agency (ESA) stressed the importance of space as a disruptive force in society and defence in its space strategy report, ‘Revolution Space’. “Countries… that wi ...

-038.jpg/fit-in/500x500/filters:no_upscale())

)

)

)

)

)