The Council on Geostrategy’s latest Britain’s World article by Peter Watkins analyses the UK’s evolving nuclear posture, from NATO’s DCA role to deepened Franco-British deterrence cooperation amid rising threats.

The UK's nuclear policy, posture and capabilities have changed little over the decades. The policy, restated in almost identical terms in successive policy documents, has been to maintain an ‘independent, minimum, credible nuclear deterrent’; to deter ‘the most extreme threats to our national security and way of life’.

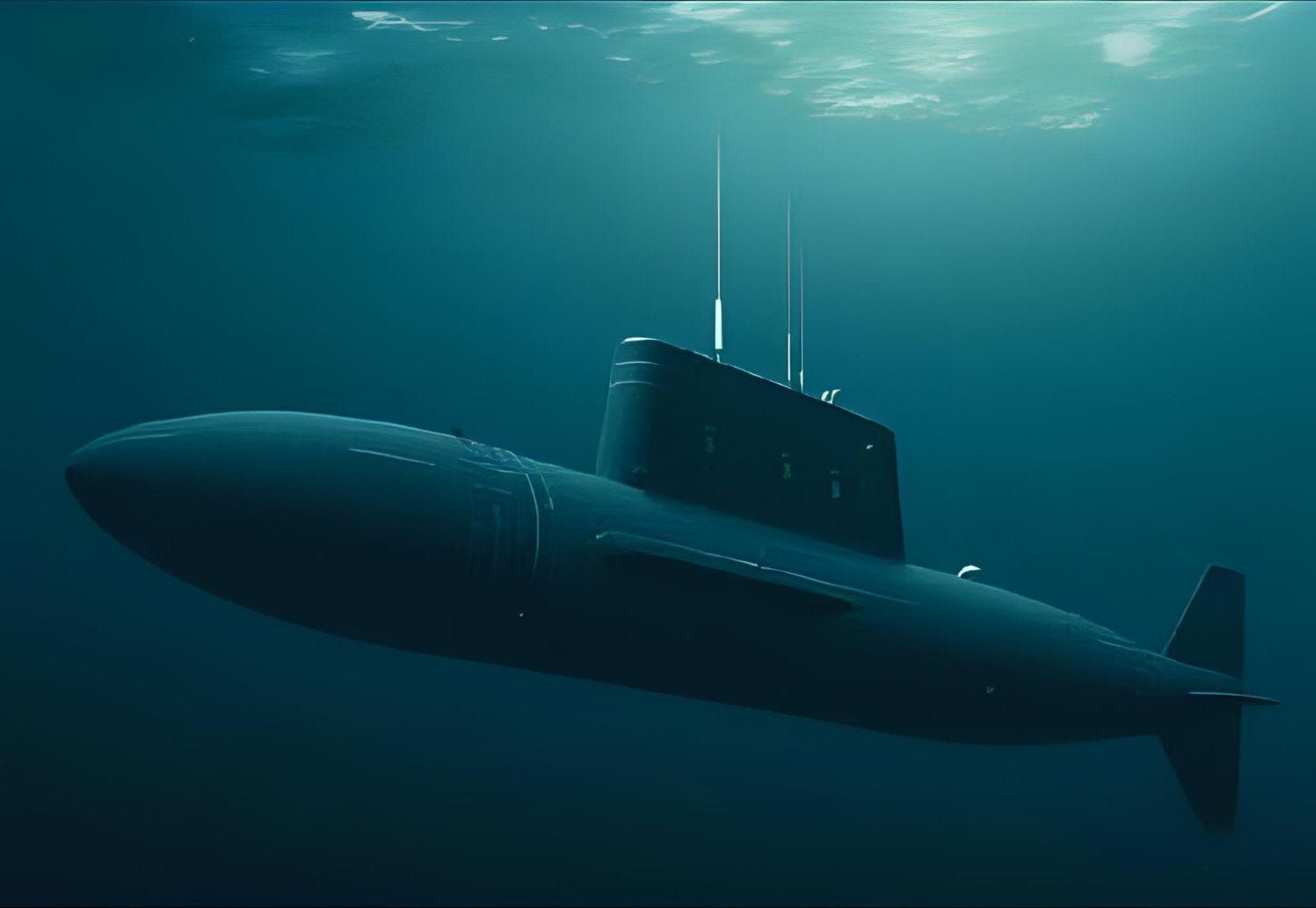

Since the late 1990s, and uniquely among the recognised nuclear powers, the British nuclear deterrent has had only one delivery system – a strategic nuclear force providing a Continuous At-Sea Deterrent (CASD). This is done through four nuclear-armed submarines (one on patrol at all times) carrying Trident ballistic missiles sourced from the US with UK-manufactured warheads. For a while, successive British governments claimed that this force also had a sub-strategic role, but little has been said about that recently.

The UK’s strategic nuclear force is operationally independent, but assigned to NATO and supported through extensive cooperation with the US, as well as more limited technological cooperation with France. The only significant recent adjustment in the posture was a relatively minor increase in the overall ceiling on the warhead stockpile in March 2021 following two decades of reductions.

This largely constant picture has changed over the past month through two major decisions. On 24 June, the UK Government announced that Britain would join NATO’s Dual Capable Aircraft (DCA) arrangements, pledging to procure 12 F-35A Lightning II Joint Combat Aircraft able to carry American B-61 nuclear bombs – a decision which it described as representing the ‘biggest strengthening of the UK’s nuclear posture in a generation’.

US Air Force F-35A Lightning II jets at RAF Marham in September 2024. (UK MoD Crown Copyright 2024)

Unstated, but not missed by commentators, was that these aircraft would also give Britain a delivery system for a sovereign sub-strategic weapon, should one be developed in future.

Then, on 10 July, the UK and France signed the Northwood Declaration, which states that their nuclear deterrents ‘can be coordinated’ and that ‘there is no extreme threat to Europe that would not prompt a response by our two nations’.

Unlike the DCA announcement, no concrete details were given on what was entailed by both governments deciding to ‘deepen their nuclear cooperation and coordination’. But, taken together, these statements mark a significant shift.

Both these decisions are responses to the changing geopolitical context. The first responds primarily to Russian military aggression in Europe and changes in Russian nuclear doctrine which appear to lower the threshold for nuclear use, whether sub-strategic or tactically employing lower-yield warheads.

Deterring such use involves having options to provide a credible response – and various commentators have questioned whether employing (and potentially placing at greater risk) a strategic, secure, second-strike capability such as Trident would be seen as credible in these circumstances.

The second decision responds more to a different trajectory, namely perceptions of a weakening US commitment to extended nuclear deterrence in Europe. The administration of Donald Trump, President of the US, has not called into question the nuclear commitment – and the UK Government professes no qualms about it.

But NATO has long recognised the value of the British and French strategic nuclear forces as a hedge against Soviet and later Russian misperceptions of American commitment, and has more recently explicitly endorsed the concept of ‘separate centres of decision making’ which contribute to deterrence by ‘complicating the calculations of potential adversaries’.

The Northwood Declaration’s pledge to closer coordination by the UK and France takes this one step further by signalling that in any future crisis in which US intentions seem uncertain, Moscow would need to take into account the combined capabilities and destructive power of the British and French nuclear forces.

These changes will require some rewriting of the (somewhat skimpy) accounts of the UK’s nuclear policy and doctrine in recent official documents, as well as on the Ministry of Defence’s (MoD) website. But much stays unchanged. The fundamental purpose of Britain’s nuclear deterrent remains defensive: the UK Government has repeatedly stated that it would consider employing its nuclear weapons "only in extreme circumstances of self-defence".

There is no indication of – and no need for – a change to that. Likewise, there is no suggestion of any relaxation in the requirement for a secure second-strike capability through CASD. And there is no suggestion of diverging from the policy of being ‘deliberately ambiguous’ about when, how, and at what scale the UK would use its nuclear weapons.

Finally, Britain continues to provide the negative security assurance that it will not use, nor threaten to use, its nuclear weapons against any non-nuclear state party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons that is not in material breach of its obligations under the treaty.

However, the strategic environment is becoming increasingly complicated and volatile. The recent decisions are sensible, even necessary, but are they sufficient? Faced with the vast and variegated Russian nuclear arsenal, NATO needs graduated options. Ideally, its three nuclear powers also need such options on a sovereign basis – the US and France (to some degree) have them; the UK will continue to not.

Joining NATO’s DCA mission gives the Royal Air Force (RAF) the opportunity to relearn nuclear skills and tradecraft which it has not needed for a generation. In parallel, it would be prudent for the MoD to explore the costs and industrial implications of acquiring a sovereign nuclear sub-strategic capability, and to conduct a rigorous balance-of-investment assessment of this vis-à-vis other capabilities.

The European nuclear conversation is unlikely to remain an exclusively British-French one. In this respect, it is welcome that the 2024 Trinity House Agreement between the UK and Germany contained a provision to establish a ‘dedicated sub-group on nuclear issues’.

European governments are likely to welcome the Northwood Declaration. Alternative European nuclear options have been floated recently (mainly by the commentariat), but they appear cumbersome and unmanageable. However, other governments are likely to want to know a bit more about what lies beneath the words. They may want to be able to contribute in some way to the development of doctrine; perhaps even with the provision of practical support.

The nuclear decisions of the past month constitute a major step forward. Ensuring that they reinforce deterrence and generate strategic advantage for Britain will require significant further work – and hard thinking.

Tags

- analyses

- article

- britain

- britains

- british

- cooperation

- council

- dca

- deepened

- deterrence

- deterrent

- evolving

- force

- france

- francobritish

- geostrategys

- governments

- latest

- mission

- more

- natos

- nuclear

- one

- options

- peter

- policy

- posture

- role

- strategic

- substrategic

- through

- uk

- uks

- use

- watkins

- world

Providing impartial insights and news on defence, focusing on actionable opportunities.

-

Most of those competing are US-based small businesses.

-

The RFI suggests there is a growing need in NATO to manage the sheer volumes of OSINT data being collected.

-

It comes as UK Space Command seeks to become “a more intelligent customer”.

)

)